English

Español

A Xicana Re-Vision of the Chicano Mural Movement

As a Xicana feminist scholar contributing to a social art history that re-contextualizes Chicano/a muralism, I write about Chicano muralism using a Xicana feminist “re-vision.” My positionality as a first-generation Xicana artist is an integral aspect of my visual analysis because I analyze Chicano muralism without strictly abiding to the standard of the three greats in Mexican muralism; Diego Rivera, David Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco. I am very familiar with Mexican murals not just because of my academic training but also through my upbringing as Mexican American with Mexican parents, Mexican and Indigenous grandparents, and with family members still living in Mexico. I approach the analysis of Chicano murals as uniquely their own thing — with some influence from the Mexican muralists. Typically, art historical methodologies do not involve subjectivity and identity as part of the analytical strategy of interpreting an image, which arguably is why my dissertation is a form of activism. I view and engage with the history of Chicana/o murals through a personal familiarity and not simply to objectify or distance myself from it. My visual analysis on Chicano murals incorporates a lens or perspective that emphasizes the experiences of womxn of color artists in the Chicano art movement in what I introduce as a “Xicana re-vision” of the Chicano mural movement.

The term “Xicano/a/x” is derived from what scholar Dylan A.T. Miner referred to as “Xicano/a” as people who are generally known as Chicanos or Mexican Americans but “pay particular attention to the Indigenist turn in Xicano identity and politics. From this perspective, to be Xicano is to be Indigenous. This spelling pays homage to the use by activists and artists who, for decades, have employed this spelling in reference to written Náhuatl” (Miner, Creating Aztlán, University of Arizona Press, 2014, 221). The term “Xicanista” introduced by Chicana feminist scholar Ana Castillo is defined as an “activista (female activist), when her flesh, mind and soul serve as a lightning rod for the confluence of her consciousness (not just Chicana, not activista for La Raza, not only a feminist but Chicana feminist), is the new generation of women that now has documentation of her particular history in the form of books, plays, murals, art, and even films that the culturalists have produced” (Castillo, Massacre of the Dreamers, University of New Mexico Press, 1994, 100-101).

The use of the term Xicano/a/x compared to Chicano/a/x is a complicated debate that continues today in academic and public forums. I intentionally use the term Xicana/x because of my connection to indigeneity through my grandparents, my academic training, and to respectfully acknowledge Indigenous people, language, and culture as American art. In addition, I write about womxn of color as artists, activists, but also as the protagonists of the Chicano art movement. My inquiries revolve around the general history of Chicano murals. What is the known history of womxn artists/muralists in the Chicano art movement since the mid 1960s? What are portable murals? What imagery and materials are used to create the portable murals? The early period of “Chicano muralism,” or the Chicano mural movement, between 1966 to 1970 was described by art historian Alan W. Barnett as Chicano “community murals” that were a form of “activism with a direct impact on the notion of identity, socio-political issues, and community outreach” (Barnett, Community Murals: The People’s Art, Art Alliance Press, 1984, 65). As the Chicano movement gained momentum art historian Shifra M. Goldman described the art movement as a “grassroots explosion” of artistic production which could be considered a “Chicano Renaissance.” Goldman compared the Chicano art and mural movement to the Harlem Renaissance (Goldman, Dimensions of the Americas, University of Chicago Press, 1994, 300).

During this “Chicano Renaissance '' period, from the late 1960s to the early 1970s, the creative strides made by womxn artists, some of which became full-time muralists while others produced murals occasionally, must be accounted for. For example, Chicana artist Carlotta d.R. Espinoza produced two portable murals on canvas titled Mujeres Heroes (Women Heroes) now destroyed and a surviving mural titled A Tribute to Three Mexican Heroes. Both murals were created in Colorado as a response to the Chicano Movement in Denver as early as 1968. I also analyze Espinoza’s portable murals alongside other womxn artists and muralists in California. This includes artists such as Judith F. Baca, Barbara Carrasco, Yreina Cervantez, who are commonly known in Los Angeles to other areas of California such as Chicana and Latina artists Carmen Léon, Juana Alicia, and Patricia Rodríguez in the San Francisco Bay Area. My research demonstrates the interconnecting ideas of the Chicano art movement, showcasing the possibilities of social justice and self-representation within each mural, but also acknowledging the artist — whether they identify as Chicana/x, Latina/x, Mexican, Mexican American, Hispanic, Indigenous, or Central American. I write womxn artists and muralists into Chicano mural history to enrich the canon on muralism in the Americas. Mexican muralists and artists such as Aurora Reyes, Rina Lazo Wasem, and María Izquierdo also join the ranks of this elite group of womxn artists who envisioned a more just future.

As I write, I am reminded of what Chicana/x feminist scholar Gloria E. Anzaldúa wrote about Chicano/a art and the use of the Indigenous language Náhuatl to express a connection to indigeneity but also to uplift it. In the early 1990s, she wrote about her experience visiting the Denver Museum of Natural History to view the exhibition titled Aztec: The World of Moctezuma. Anzaldúa described the voice of Chicano actor Edward James Olmos narrating the audio tour speaking in Náhuatl and said, “Though I wonder if Olmos and we Chicana/o writers and artists also are misappropriating the Náhuatl language and images, hearing the words and seeing the images boosts my spirits.” She continued to add, “I feel that I am part of something profound outside my personal self. This sense of connection and community compels Chicana/o writers/artists to delve into, sift through, and re-work native imagery” (Keating ed., Anzaldúa, “Border Arte: Nepantla el luger de la Frontera,” in The Gloria E. Anzaldúa Reader, Duke University Press, 2009, 177-178). Anzaldúa’s acknowledgement of “border arte and artists” as change makers, disrupters, influencers, and original creators of their own narratives provides the foundation for new generations of Xicano/a/x artists and muralists to thrive.

Gaby R. Gomez @profeladyxoc

Una Re-visión Xicana del Movimiento Mural Chicano

Como académica feminista Xicana contribuyo a una historia del arte social que recontextualiza el muralismo, escribiendo sobre el muralismo chicano usando una “revisión” feminista Xicana. Mi posicionamiento como artista Xicana de primera generación, es un aspecto integral de mi análisis visual, debido a que analizo este muralismo sin ceñirme, estrictamente, al estándar de los tres grandes del muralismo mexicano que son: Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros y José Clemente Orozco.

Estoy muy familiarizada con los murales mexicanos, no solo por mi formación académica, sino también por mi educación como mexicoamericana con padres mexicanos, abuelos mexicanos e indígenas y con familiares que aún viven en México. Me acerco al análisis de los murales como algo exclusivamente propio, con cierta influencia de los muralistas mexicanos. Por lo general, las metodologías en la historia del arte no involucran la subjetividad y la identidad como parte de la estrategia analítica para interpretar una imagen, lo que podría decir el por qué mi disertación es una forma de activismo.

Veo y me comprometo con la historia de los murales de Chicana/o, a través de una familiaridad personal y no simplemente para objetivarme o distanciarme de ella. Mi análisis visual de estas obras, incorpora una lente o perspectiva que enfatiza las experiencias de las mujeres artistas de color en el movimiento de arte chicano, en lo que presento como una “re-visión Xicana” del Movimiento Mural Chicano.

El término “Xicano/a/x” se deriva de lo que el erudito Dylan A.T. Miner definió como “Xicano/a” para referirse a las personas que, generalmente, son conocidas como chicanos o mexicoamericanos pero que “prestan especial atención al giro indigenista en la identidad y la política de los Xicanos. Desde esta perspectiva, ser Xicano es ser indígena. Esta ortografía rinde homenaje al uso que, durante décadas, activistas y artistas han empleado en referencia al náhuatl escrito” (Miner, 2014, p. 221).

El término “Xicanista”, introducido por la estudiosa feminista chicana Ana Castillo, se define como una “activista (mujer activista), cuando su carne, mente y alma sirven como un pararrayos para la confluencia de su conciencia (no solo chicana, sino activista para La Raza, no solo feminista, sino feminista chicana), es la nueva generación de mujeres que ahora tiene documentación sobre su historia particular en forma de libros, obras de teatro, murales, arte e incluso películas que han producido los culturalistas” (Castillo, 1994, pp. 100-101).

El uso del término Xicano/a/x en comparación con Chicano/a/x, es un debate complicado que continúa hoy en foros académicos y públicos. Utilizo intencionalmente el término Xicana/x debido a mi conexión con la indigeneidad a través de mis abuelos, mi formación académica y para reconocer respetuosamente a los pueblos, los idiomas y las culturas indígenas como arte estadounidense. Además, escribo sobre mujeres de color como artistas, activistas, pero también, como protagonistas del movimiento de arte chicano. Mis consultas giran en torno a la historia general de los murales chicanos: ¿Cuál es la historia conocida de las mujeres artistas/muralistas del movimiento de arte chicano desde mediados de la década de 1960? ¿Qué son los murales portátiles? ¿Qué imágenes y materiales se utilizan para crear los murales portátiles?

El período inicial del “muralismo chicano” o el Movimiento Muralista Chicano, entre 1966 y 1970, fue descrito por el historiador de arte Alan W. Barnett como “murales comunitarios” chicanos que eran una forma de “activismo con un impacto directo en la noción de identidad, cuestiones sociopolíticas y de alcance comunitario” (Barnett, 1984, p. 65). A medida que el movimiento chicano ganaba impulso, la historiadora del arte Shifra M. Goldman, lo describió como una “explosión de base” de producción artística que podría considerarse un “Renacimiento Chicano”. Goldman comparó el arte chicano y el movimiento mural con el Renacimiento de Harlem (Goldman, 1994, p. 300).

Durante este período del “Renacimiento Chicano”, se deben tener en cuenta los avances creativos realizados por mujeres artistas, algunas de las cuales se convirtieron en muralistas de tiempo completo, mientras que otras produjeron murales ocasionalmente. Por ejemplo, la artista chicana Carlotta D.R. EspinoZa produjo dos murales portátiles sobre lienzo titulados: Mujeres Héroes ahora destruidos y un mural sobreviviente titulado: A Tribute to Three Mexican Heroes. Ambos fueron creados en Colorado como respuesta al Movimiento Chicano en Denver desde 1968.

También analizo los murales portátiles de EspinoZa junto con otras mujeres artistas y muralistas en California, que incluye a artistas como: Judith F. Baca, Barbara Carrasco, Yreina Cervantez, quienes son comúnmente conocidas en Los Ángeles y, en otras áreas de California, como las artistas chicanas y latinas: Carmen León, Juana Alicia y Patricia Rodríguez en el Área de la Bahía de San Francisco. Mi investigación demuestra las ideas interconectadas del movimiento de arte chicano, mostrando las posibilidades de justicia social y autorrepresentación dentro de cada mural, pero también reconociendo al artista, ya sea que se identifique como chicana/x, latina/x, mexicana, mexicoamericana, hispana, indígena o centroamericana. Escribo a mujeres artistas y muralistas sobre la historia del mural chicano para enriquecer el canon sobre el muralismo en las Américas. Muralistas y artistas mexicanas como Aurora Reyes, Rina Lazo Wasem y María Izquierdo también se suman a las filas de este grupo élite de mujeres artistas que imaginaron un futuro más justo.

Mientras escribo, recuerdo lo que la estudiosa feminista chicana/x Gloria E. Anzaldúa plasmó sobre el arte chicano/a y el uso de la lengua indígena náhuatl, para expresar una conexión con la indigeneidad, pero también para elevarla. A principios de la década de 1990, escribió sobre su experiencia al visitar el Museo de Historia Natural de Denver para ver la exposición titulada: Aztec: The World of Moctezuma. Anzaldúa describió la voz del actor chicano Edward James Olmos al narrar la audioguía hablando en náhuatl y dijo: “Aunque me pregunto si Olmos y nosotros, los escritores y artistas chicanos/x, también nos estamos apropiando indebidamente del idioma náhuatl y de las imágenes, escuchando las palabras y viendo las imágenes, levanta mi ánimo”. Continuó agregando: “Siento que soy parte de algo profundo fuera de mi ser personal. Este sentido de conexión y comunidad obliga a los escritores/artistas chicanos/as a profundizar, tamizar y reelaborar las imágenes nativas” (Keating ed., Anzaldúa, 2009, pp. 177-178). El reconocimiento de Anzaldúa del “arte y los artistas fronterizos” como creadores de cambios, disruptores, influyentes y creadores originales de sus propias narrativas, proporciona la base para que prosperen las nuevas generaciones de artistas y muralistas Xicano/a/x.

We are Not a Minority

1978

Congreso de Artistas Chicanos en Aztlan (Mario Torero with Zapilote, Rocky, el Leon) Zade

Los Angeles, California

The Great Wall of Los Angeles

1974

Judith F. Baca

Los Angeles, California

The Great Wall of Los Angeles

1974

Judith F. Baca

Los Angeles, California

The Great Wall of Los Angeles

1974

Judith F. Baca

Los Angeles, California

The Great Wall of Los Angeles

1974

Judith F. Baca

Los Angeles, California

The Great Wall of Los Angeles

1974

Judith F. Baca

Los Angeles, California

The Great Wall of Los Angeles

1974

Judith F. Baca

Los Angeles, California

The Great Wall of Los Angeles

1974

Judith F. Baca

Los Angeles, California

Ramona Lisa

n.d. | s.f.

Levi Ponce

Los Angeles, California

Untitled (Homeboy)

1974

Manuel Cruz

Los Angeles, California

Latinoamerica

1974

Las Mujeres Muralistas (Patricia Rodriguez, Graciela Carrillo, Consuelo Mendez, Irene Perez)

Los Angeles, California

La Ofrenda

1989

Yreina Cervantez

Los Angeles, California

Hecho a Mano

2020

Sonia Romero Photographer: Elon Schoenholz

Los Angeles, California

Hecho a Mano

2020

Sonia Romero Photographer: Elon Schoenholz

Los Angeles, California

Lady of the Valley

2001

Levi Ponce and Ernie "Serv One" Rojas. Photographer: Javier Martinez

Los Angeles (Pacoima), California

La Familia

1977

Wayne Alaniz-Healy and David Rivas Botella

Los Angeles, California

Chicano History mural

1970

Eduardo Carrilo, Sergio Hernandez, Ramses Noriega, and Saul Solache

Los Angeles, California

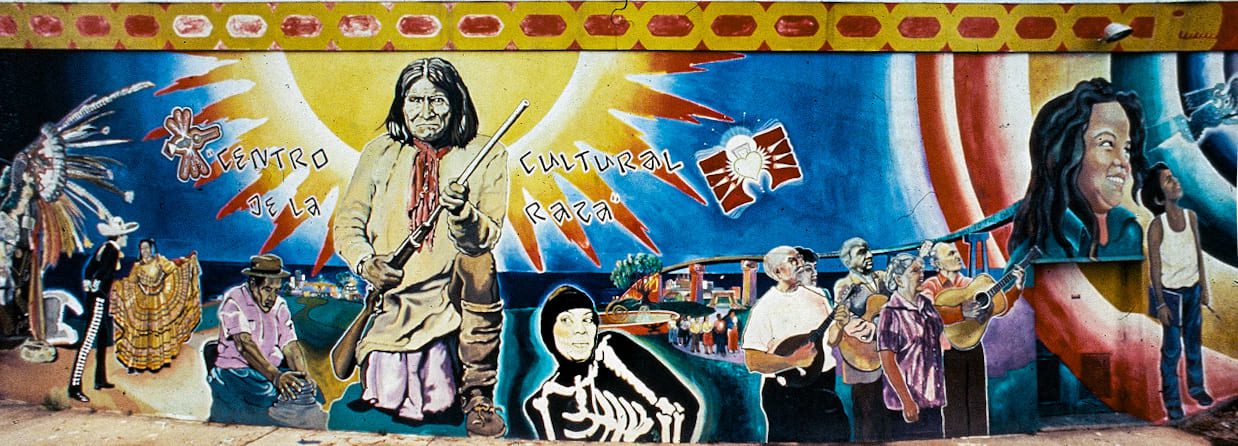

Geronimo

1981

Victor Ochoa

San Diego, California

Laura Rodriguez

n.d.

Mario Torero

San Diego, Chicano Park, California

The Return of Quetzalcoatl

1973

CACA Congreso de Artistas Chicanos en Aztlán

San Diego, Chicano Park, California

Kiosko

n.d.

Alfredo Larin and Chicano Park Community

San Diego, Chicano Park, California

Luna Bliss

2018

Victor Marka27 Quiñonez

Lynn, Massachusetts

Las Lechugueras

2000s

Juana Alicia

San Francisco, California

Huitzilophochtli

2009

David Ocelotl Garcia

Denver, Colorado

La Antorcha de Quetzalcoatl

n.d.

Leo Tanguma

Denver, Colorado

Façade

n.d.

Carlos Fresquez & MSU Students from “Community Painting: The Mural” Course

Denver, Colorado

Homage to Peoria's Past

2009

Emanuel Martinez

Denver, Colorado

Staff of Life

1976

Emanuel Martinez

Denver, Colorado

Neo Indigenous

2016

Victor Marka27 Quiñonez

Denver, Colorado

Song of Unity

1978

Common Arts (Ray Patlan, Osha Neumann, Anna de Leon, O’Brien Thele)

Berkeley, California

Alma Indigena

2021

Victor Marka27 Quiñonez

Washington, DC

Mayahuel

2001

Rock Martinez

Tucson, Arizona

Corazon Del Pueblo

2011

David Ocelotl Garcia

Pueblo, Colorado

American Painting

2013

Gabriel Villa

Chicago, Illinois

Searching for Mentors in Memories

2016

Sam Kirk

Chicago, Illinois

Declaration of Immigration

2009

Salvador Jiménez

Chicago, Illinois

Declaration of Immigration

2009

Salvador Jiménez

Chicago, Illinois

Cucurrucucú My Love

n.d.

Chema Skandal

Chicago, Illinois

Cucurrucucú My Love

n.d.

Chema Skandal

Chicago, Illinois

Southside Park Mural

Original 1969 - Restored 1977

Royal Chicano Air Force

Sacramento, California

1846 We are Indigenous, Not Illegal

2020

Victor Marka27 Quiñonez

Boulder, Colorado

Virgen Indigena

2004

Jane Madrigal, Jose Cosme, & Louie Alejandro

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

Leyendas Aztecas

1998

Israel “Izzy” Rico

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

Familia y Cultura

Original 1995 - Restored 2011

Debbie Esparza, Juan Ramos, Andy Rivas, Angel Hernandez, Brandy Salinas, Eduardo Urbano, Enrico Salinas, Jessica Garcia, Juan Francisco, Ruben Serafin

Damien Salkin & youth team

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

Tradición y Cultura

Original 2001 - Restored 2018

Alex Rubio, Ruth Buentelo, Oscar Flores, Damien Hernandez, Victor Mena

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

8 Stages of a Chicana

Original 1995 - Restored 2004 and 2017

Cruz Ortiz, Carlos Espinoza, Cardee, Gerry Garcia, Adriana Abundis & Youth volunteers

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

Educacion

Original 1994 - Restored 1999

Adrian "El Caminante" Cervantez, Carlos Herandez, Manuel "MEME" Castillo, Rina "Taco Lady" Moreno, Patti "Bunkhaus" Radle, Luna family siblings, Mike Kokinda; youth volunteers: Angela, "El Bob," El Necio Kid, Ricardo, Emilio, Rebecca Lopez, Eric

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

Educacion

Original 1994 - Restored 1999

Adrian "El Caminante" Cervantez, Carlos Herandez, Manuel "MEME" Castillo, Rina "Taco Lady" Moreno, Patti "Bunkhaus" Radle, Luna family siblings, Mike Kokinda; youth volunteers: Angela, "El Bob," El Necio Kid, Ricardo, Emilio, Rebecca Lopez, Eric

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

Comprando

Original 1996 - Restored 2007

Mary Helen Herrera, Ricardo Islas, Cardee Garcia, Gerry Garcia, David Blancas, Ruth Buentello, Alvaro Ramirez, Patrick Luna, Alejandro Garcia, Victor "Supher" Zarazua

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

Una Mesa Para La Gente

Original 1999 - Restored 2008

Cruz Ortiz, Lisa Veracruz, Ruth Buentello, San Antonio Youth Centers, House of Teens, Fuerza Unida Youth, Southwest Workers YLO, Cardee Garcia, Gerry Garcia, Ana Cavasos, Joseph Cavasos, Melinda Higgins, Imelda, Alejandro Padilla, Fabian Diaz, Adriana Garcia, Rico Salinas, Daisy Hernandez, Yasmin Codina, Clarissa Duran, Charlie, Ricardo Briones, Maricela Olguin, Celeste DeLuna, Alejandro, Cristina Ordonez, Arturo Morales, Eddie Chavez, Michaela Jacobson, Serenity Hernandez

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

Insomne de Amor

Original 1999 - Restored 2008

Rigoberto Luna, Ruth Buentello Restoration crew members: Bianca Arguellez, Brian Arista, Kim Bishop, David Blancas, Celeste de Luna, Adriana Garcia, Alejandro Garcia, Cardee Garcia, Christian Rodriguez, Alex Rubio, Alexandra Salinas, Enrico "Caso" Salinas, Julio Trevino

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

Mano a Mano

1999

Juan Ramos, Mike Roman, Janette Torres

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

Basta Con La Violencia

1997

Israel "Izzy" Rico

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

Guadalupe Cultural Arts Centre

n.d.

Jesse Treviño

San Antonio, Texas

End Barrio Warfare

Original 1998 - Restored 2010

Augustine "Fugi" Villa, Lisa Mendiola

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

Justice for Vanessa

2020

Ana Hernandez Burwell

San Antonio, Texas

Rebirth of a Nationality

Original 1973 - Restored 2018

Leo Tanguma

Houston, Texas

Rebirth of a Nationality

Original 1973 - Restored 2018

Leo Tanguma

Houston, Texas

Rebirth of a Nationality

Original 1973 - Restored 2018

Leo Tanguma

Houston, Texas

Trinity

2016

Victor Marka27 Quiñonez

Worcester, Massachusetts

Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles (Pacoima), California

Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles, California

San Diego, California

San Diego, Chicano Park, California

San Diego, Chicano Park, California

San Diego, Chicano Park, California

Lynn, Massachusetts

Juana Alicia

San Francisco, California

Denver, Colorado

Denver, Colorado

Denver, Colorado

Denver, Colorado

Denver, Colorado

Denver, Colorado

Berkeley, California

Washington, DC

Tucson, Arizona

Pueblo, Colorado

Chicago, Illinois

Chicago, Illinois

Chicago, Illinois

Chicago, Illinois

Chicago, Illinois

Chicago, Illinois

Sacramento, California

Boulder, Colorado

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

San Antonio, Texas Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

San Antonio, Texas

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy of San Anto Cultural Arts

San Antonio, Texas

Houston, Texas

Houston, Texas

Houston, Texas

Worcester, Massachusetts